Revive & Restore and the Hawaii Exemplary State Foundation convened 42 scientists, policymakers, and community organizers from key conservation organizations and government agencies in September 2016 to explore strategic approaches to eliminate from Hawaii mosquito-borne diseases, which harm human health and local biodiversity.

Their recommendations formed the basis of a recently published white paper – “Restoring a Mosquito-Free Hawaii” – that will be an essential document for promoting and pursuing the next steps in achieving the suppression and (hopefully) the elimination of mosquito-borne diseases on the Hawaiian Islands. (Scroll down to the bottom of the page to read the report in full.)

Participants of the two-day workshop concluded that engaging the public, developing the science, and putting resources to work on locally appropriate solutions are crucial to combating the serious threat of mosquito-transmitted diseases and to protecting both Hawaii’s public health and unique biodiversity. Close to ninety percent of native Hawaiian plants are threatened with extinction, according to estimates made by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (I.U.C.N). Hawaii’s avian population, including the brightly colored honeycreepers, is disappearing at an alarming rate. Of more than a hundred native bird species, just forty-two remain. Most are endangered. While climate change and invasive species of all types have played a role in the declining populations of native birds, invasive mosquitoes carrying avian malaria are the principal threat.

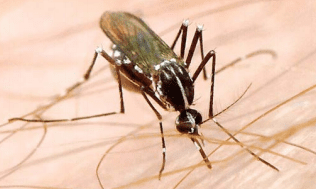

Mosquitoes are not endemic to the Hawaii; they were introduced in the early 1800s via whaling ships. Because of the extreme isolation of the Hawaiian Islands, native species had not developed resistance to mosquito-borne diseases. Six separate species can now be found on the islands – two species transmit deadly human diseases (dengue, chikungunya, and Zika), while one carries the vector for avian malaria. The seriousness of these diseases and their ongoing damage to Hawaii’s public health, native forest birds, culture, and economy have galvanized interest in new techniques to combat mosquitoes in Hawaii.

The report explains:

“Standard mosquito control methods cannot permanently suppress or eradicate mosquitoes in Hawaiʻi. They are too costly, labor intensive, and often employ non-specific pesticides all of which are not effective or appropriate in rural and especially remote roadless forests where disease-sensitive native birds live. However, novel approaches offer new hope to control and even eliminate mosquitoes in Hawaiʻi. Recent dengue outbreaks, combined with the threat of a local Zika virus epidemic, highlight Hawaiʻi’s vulnerability to mosquito-borne pathogens and have galvanized efforts to look beyond standard methods to minimize the risk of mosquito-borne diseases in the islands. Removing mosquitoes from the Hawaiian Islands would eliminate the threat of vector-borne diseases that currently impact human and native forest bird populations.”

Mosquito Species

Both transmit dengue, chikungunya, and Zika virus

Aedes albopictus / Photo: Durrell D. Kapan

Aedes aegypti / Photo: Durrell D. Kapan

Novel approaches to suppressing or eradicating mosquitoes include new applications of the Sterile Insect Technique, where male mosquitoes –made sterile by either irradiation or the unique insect-specific bacteria Wolbachia – are released to mate with local females, causing the population to crash. These two methods of sterilization can also be combined for optimal results. The final method explored at the workshop uses genomic technology to create “self-limiting” mosquitoes. To create these self-limiting mosquitoes, a gene is introduced that stops cells from functioning normally. Male mosquitoes with this edited gene are released to mate with local female, but their offspring are unable to develop to adulthood due to this modification. Because the mosquitoes do not survive into adulthood, the gene does not persist in the environment, hence the “self-limiting” name.

Organizers

2016 IUCN World Conservation Congress, American Bird Conservancy, California Academy of Sciences, Hawaiʻi Department of Health, Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources, Hawaiʻi Exemplary State Foundation, Office of the Mayor of Hawaiʻi County, Revive & Restore, United States National Park Service, United States Fish and Wildlife Service, United States Geological Survey, University of Hawaiʻi-Hilo, University of Hawaiʻi-Manoa.

Participants

Mary M. Abrams, PhD; Carter T. Atkinson, PhD; Shannon Bennett, PhD; Stewart Brand; Richard P. Creagan, MD; Prof. Stephen L. Dobson, PhD; Prof. Kevin Esvelt, PhD; Chris Farmer, PhD; Joshua P. Fisher; Kevin Gorman, PhD; Eric Honda; Darcy Hu, PhD; Christopher Jacobsen; Prof. Anthony A. James, PhD; Prof. Kenneth Y. Kaneshiro, PhD; Durrell D. Kapan, PhD; Cynthia B. King, MS; Dennis A. LaPointe, PhD; Prof. James V. Lavery, PhD; Elaine F. Leslie; Prof. Matthew C.I. Medeiros, PhD; Stephen E. Miller, PhD; Ryan J. Monello, PhD; Kevin Montgomery, PhD; Neil I. Morrison, PhD; Jack D. Newman, PhD; Samantha M. O’Loughlin, Ph.D; Eben H. Paxton, PhD; Ryan Phelan; Gordana Rasic, PhD; Kent H. Redford, PhD; Floyd A. Reed, PhD; Michael Specter; Prof. Jolene Sutton, PhD; David F. Tessler; Ed Teixeira; Prof. Michael Turelli, PhD; John P. Vetter; Adam E. Vorsino, PhD; Renee D. Wegrzyn, PhD; Prof. Zhiyong Xi, PhD; Aubrey M. Yee