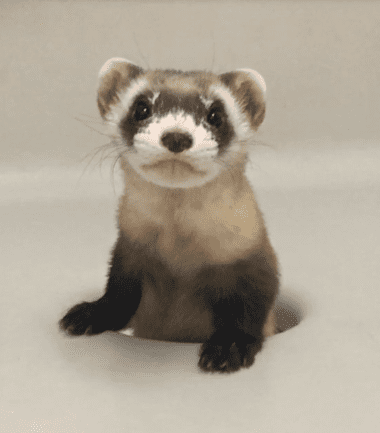

Photo: Cloned black-footed ferret Noreen, born in 2023, plays in her enclosure at the National Black-Footed Ferret Conservation Center. Credit: Revive & Restore

Black-Footed Ferret Recovery

Twice considered extinct, black-footed ferrets (Mustela nigripes) were rediscovered in 1981 and today are the focus of a broad recovery effort. Captive breeding, reintroductions, and habitat protection have helped restore ferret populations to over 300 animals in the wild. However, all living ferrets descend from just seven individuals, compromising long-term recovery efforts.

Since 2013, Revive & Restore and its partners have worked to restore genetic diversity in black-footed ferrets through strategic conservation cloning. We welcomed the world’s first cloned black-footed ferret in 2020, and two additional cloned ferrets in 2023. We are simultaneously working to facilitate heritable disease resistance to sylvatic plague – a major threat to recovery in the wild.

About the project

Black-footed ferrets are the only ferret native to North America and one of the most endangered mammals in the world. The species was twice assumed extinct, before being rediscovered in 1981 by a ranch dog named “Shep” in Meeteetse, Wyoming. The discovery of the last remaining ferret population launched a captive breeding program by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) to safeguard the species from extinction.

While ongoing breeding and reintroduction efforts have helped rebuild population numbers, the founding population was only seven individuals. Thus, restoring genetic variation is essential to ensure the species’ long-term adaptation and survival.

One individual from the captive population, a female named Willa, never bred in captivity. When she died in 1988, her tissue was cryopreserved at the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Frozen Zoo® for future restoration efforts. She is genetically distinct from the living population of black-footed ferrets, creating the opportunity for genetic rescue.

In 2013, Revive & Restore, the USFWS, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, and ViaGen Pets and Equine launched a collaboration to clone a black-footed ferret from Willa’s frozen cells. The world’s first successfully cloned black-footed ferret, Elizabeth Ann, was born on December 10, 2020, marking the first time a U.S. endangered species had been successfully cloned.

In May 2023, two additional cloned black-footed ferrets were born from the same cell line. The ferrets, named Noreen and Antonia, are Elizabeth Ann’s genetic twins. Noreen was born at the National Black footed Ferret Conservation Center, while Antonia was born at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute in Virginia. While Elizabeth Ann is not able to breed due to a medical condition, Noreen and Antonia may become the first cloned animals to restore lost genetic variation to their species.

“Genomics revealed the genetic value that Willa could bring to her species. But it was a commitment to seeing this species survive that has led to the successful birth of Elizabeth Ann. To see her now thriving ushers in a new era for her species and for conservation-dependent species everywhere. She is a win for biodiversity and for genetic

rescue.”

Ryan Phelan

Executive Director, Revive & Restore

OVERCOMING A GENETIC BOTTLENECK

Noreen, Antonia, and Elizabeth Ann are clones of “Willa,” a wild-caught black-footed ferret whose cell line was cryopreserved in 1988. A 2014 genomic study by Revive & Restore helped determine that Willa’s genome held nearly three times more genetic diversity than the current black-footed ferret population. This means that clones from Willa’s historic cell lines can enrich the present day gene-pool of this endangered species.

Watch the video: Learn how Elizabeth Ann came to be, as told by project partners.

Project news & updates

Filter

Major Project Milestones

2024

NOREEN AND ANTONIA ARE ANNOUNCED

Revive & Restore and partners announce the birth of two black-footed ferret clones, named Noreen and Antonia. Noreen was born at the National Black footed Ferret Conservation Center, while Antonia resides at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute in Virginia. Both were cloned from the same genetic material as Elizabeth Ann.

2022

ELIZABETH ANN IS TREATED FOR HYDROMETRA

Elizabeth Ann reached sexual maturity in the Spring of 2022 and as expected went into estrus at 16 months of age. However, during an artificial insemination attempt, it was discovered that Elizabeth Ann had developed a uterine condition, hydrometra, that prevented her from being able to breed this year. She had an ovariohysterectomy performed. Fortunately, Elizabeth Ann has made a full recovery from surgery and is in good health.

2021

ELIZABETH ANN IS ANNOUNCED TO THE WORLD

Revive & Restore and partners announce the birth of Elizabeth Ann, the world’s first cloned black-footed ferret. Elizabeth Ann was created from the frozen cells of “Willa,” a black-footed ferret that lived more than 30 years ago. A genomic study revealed Willa’s genome possessed three times more unique variations than the living population. Therefore, if Elizabeth Ann successfully mates and reproduces, she could provide unique genetic diversity to the species.

2019

CLONING RESEARCH BEGINS

Concerted laboratory work begins, supported through our Catalyst Science Fund began. Cloned Black-footed ferret embryos were successfully created in vitro, which showed that domestic ferret oocytes are compatible with Black-footed ferret genomes. This was the first promising step in validating the use of interspecies cloning for genetic rescue.

2018

PERMIT RECEIVED

Revive & Restore received an Endangered Species Recovery Permit from the United States Fish & Wildlife Service after our application passed public review in compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). This first-of-its-kind authorization permitted the laboratory work necessary to demonstrate that the genetic rescue of Black-footed ferrets is feasible. Specifically, the permit allowed Revive & Restore and our partners to conduct two principal activities. First, determine the potential for using iSCNT cloning techniques to bring genetic diversity from historic cell lines back into the population. Second, it permitted Revive & Restore and our partners to test a variety of hypothetical sylvatic plague resistance solutions in cell culture.

2014

THE GENOMICS WORKING GROUP IS FORMED

Revive & Restore and the Black-footed Ferret Implementation Team (BFFRIT) met in person for the first time at the National Black-footed Ferret Conservation Center (NBFFCC). During the meeting, they formed the Genomics Working Group, which has continued to set annual meetings to coordinate the genetic rescue and genomic management of the Black-footed ferret. In partnership with the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Frozen Zoo® and Cofactor Genomics Revive & Restore initiated the building of a Black-footed ferret genomic database. We started by sequencing the genomes of Willa, SB2, Cheerio, and Balboa to measure the amount of genetic diversity we could expect to gain by genetic rescue efforts.

2013

A PARTNERSHIP FOR GENETIC RESCUE BEGINS

After seeing our TEDxDeExtinction event online, Seth Willey from the United States Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) invited Revive & Restore to explore the potential use of genomic technologies to increase Black-footed ferret genetic diversity. The potential to clone new founders and use gene-editing technologies to develop plague resistance were discussed in those earliest meetings.