ABOUT THE SPECIES

The Przewalski’s horse (Equus przewalskii) is considered the last truly wild horse species. They are the descendants of a lineage that diverged from that of the domestic horse lineage (Equus caballus) hundreds of thousands of years ago. With almost 2000 total living individuals, half of them living in zoos, the stocky horse with its short erect mane is rarer than the giant panda. Once listed as extinct in the wild, careful captive breeding programs and reintroductions to their native habitat in the arid steppe of Mongolia and China have given this horse a new chapter in its long story of survival. But genetic diversity is lacking. Now a project of Revive & Restore, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, and Viagen Pets and Equine may help the species once again.

A BRUSH WITH EXTINCTION

Przewalski’s horses are native to what is called the steppe. Until 15,000 years ago, this grassland habitat stretched from Asia to present-day Portugal. After the last Ice Age, however, the steppe gave way to woods and forests, and by the 19th century, the Przewalski’s horses remained only in Mongolia, southern Russia, and Poland. The Przewalski’s horse got its name from a Russian explorer, Colonel Nikolai Przhevalsky (pronounced “shuh-VAL-skee”). It has been said that the colonel was the first to scientifically describe the horse, yet it had been discovered and described earlier. Nevertheless, the distinctive name stuck.

The Mongolians call the horse by another name takhi, which means “spirit,” or “worthy of worship.” While the region’s own domestic horse has been central to Mongolian culture since the time of Ghengis Kahn, the swift and elusive takhi was respectfully left to its own devices.

By the Twentieth Century, however, its petite size, stocky shape, cropped mane, and shedding woolly winter coat—all adaptive traits for survival on the steep slopes, harsh winters and scorching summers of Mongolia—drew interest from many Europeans including Carl Hagenbeck, a German merchant trading in exotic animals to zoos and circuses.

In “The Remarkable Comeback of the Przewalski’s Horse,” writer Paige Williams describes what happened next: “Hagenbeck, by his own count, took at least 52 foals. Expeditions to catch the takhi lasted for about 20 years. When capturing the foals, hunters often killed the stallions, which then jeopardized natural breeding. In the meantime, deadly winters killed thousands of horses, and overgrazed pastures left others starved. Mongolia’s last group of takhi was spotted around 1969. Then, as far as anyone could tell, the creature ceased to exist in the wild.”

RECOMMENDED READING

The Last Truly Wild Horses Are Alive and Well in Chernobyl

Popular Mechanics, 2019

The Remarkable Comeback of Przewalski’s Horse

Smithsonian Magazine, 2016

10 Things You Didn’t Know About Przewalski’s Horses

Scientific American, 2014

The Asiatic Wild Horse

Erna Mohr. J. A. Allen & Co. Ltd., 1971

LESSONS IN CAPTIVE BREEDING

All Przewalski’s horses alive today are descended from just 12 wild-caught individuals, and as many as four domestic horse founders, which became the nucleus of what would become a captive breeding program. At first, the horses didn’t do very well in captivity. But in 1959, a studbook was assembled. It was found that of the 53 animals recorded as having been brought into zoological collections in the west, fewer than 25% had contributed any genes to the living population.

In North America, that breeding program is now managed by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) Species Survival Plan (SSP). Since the SSP was formed in 1981, the number of institutions that keep and breed the species has shrunk by half. Furthermore, roughly 60% of the original genetic diversity in the breeding program has been lost.

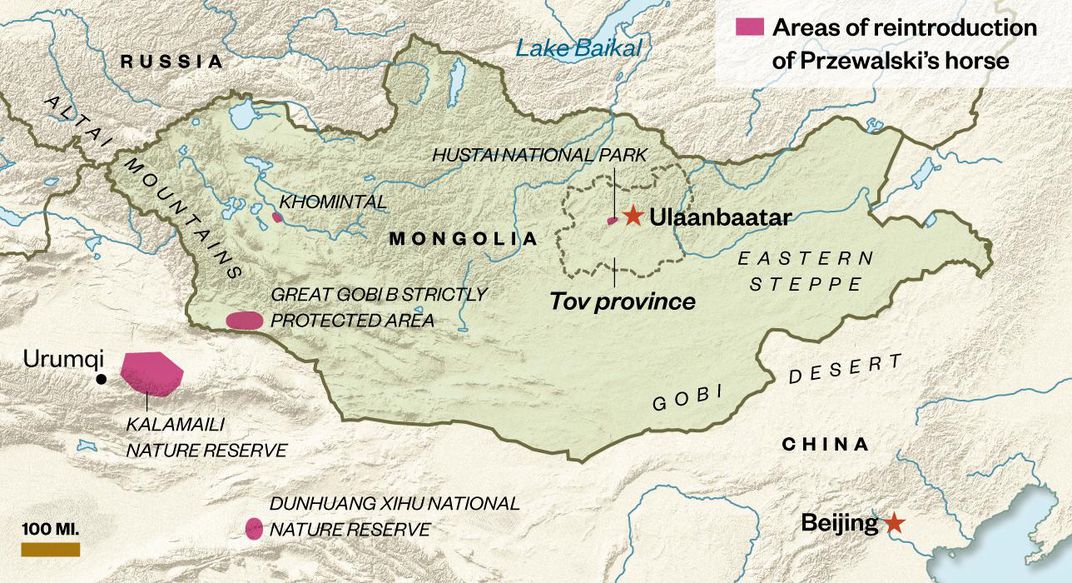

Despite these challenges, this species continues to survive—and multiply. Captive breeding led to reintroductions of the species in Mongolia and China. There are now approximately 387 native-born Przewalski’s Horses in Mongolia at three reintroduction sites; the Great Gobi B Strictly Protected Area (SPA), Hustai National Park, and Khomiin Tal. In China, populations have been re-established at the Kalamaili Nature Reserve (KNR) and Dunhuang Xihu National Nature Reserve. Other populations are living in reserves across Europe and Eurasia—including 60 horses thriving in the Chernobyl exclusion zone.

In 2008 the IUCN reclassified the Przewalski’s horse from extinct-in-the-wild to critically endangered. In 2011 their status was changed to endangered. But due to the fragmented and small population sizes, habitat degradation, climate change, and disease, this species remains vulnerable. Therefore, continued stewardship, across multiple countries, is necessary. New techniques of genetic rescue to help overcome the genetic bottleneck imposed upon them in the 20th Century are now being used, from artificial insemination in 2013 to the remarkable first cloning of a foal from a cryopreserved cell line in 2020.

A survivor in the care of hundreds of dedicated scientists, zoologists, conservationists, and geneticists, the Przewalski’s horse species may now regain the fitness and adaptability needed to survive in a changing world.

NATURAL HISTORY

According to San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, the horses live in two types of distinct social groups: harem and bachelor groups. Harems rarely have more than 10 mares and their offspring up to 2 or 3 years of age and are led by one dominant stallion. They all graze and rest at the same time. A lot of time is spent grooming one another to help reinforce social bonds within the group.

When young stallions are old enough to compete with the lead stallion, they are driven out of the harem. From here, they join small bachelor groups until they can successfully compete for a harem group of their own. When mares are old enough to reproduce, they may leave the harem group to join another. Foals are born after an 11-month gestation period, and they must be up and moving with the herd about 30 minutes after birth. By one week of age, foals are eating grasses and practicing their kicking skills. At one month of age, foals begin to play with other foals and older siblings in the herd. By two months, they begin to venture away from the protection of their mothers. Young horses stay with the group they were born into until they are sexually mature.

In their natural habitat, wolves are the Przewalski’s horse’s most dangerous predator. To protect the foals, the mares form a defensive circle around the youngsters, and the stallion trots around the circle and charges. At night, one or more horses will keep watch while the others rest. Small herds are more vulnerable to attack, as there are fewer adults to protect the foals. Growing the size of the herds in the wild will be a great benefit to the species.

Areas of reintroduction include the Przewalski’s natural habitats of Mongolia and China. (Guilbert Gates, via Smithsonianmag.com)