Read our Progress to Date here.

About This Project

The Heath Hen (Tympanuchus cupido cupido) was one of the first species in the United States to draw a concerted conservation effort. Once thriving in habitats from Maine to the Carolinas, by 1870 the Heath Hen had dwindled to a single population on Martha’s Vineyard (off Cape Cod, Massachusetts), where local officials established a preserve. But the bird was extinct by 1932.

For residents of Martha’s Vineyard, the Heath Hen is the subject of much local lore. On the site of the original Heath Hen Preserve, a large stone monument has been erected in remembrance of “Booming Ben,” the last known Heath Hen, named for the bird’s vocal mating ritual as he spent his final years calling to females no longer there to hear.

The Heath Hen has been a Revive & Restore de-extinction projects since 2014. That summer, Revive & Restore held a town hall-style meeting with the Martha’s Vineyard community to discuss bringing back the extinct Heath Hen. A cadre of founding supporters formed, and they provided the enthusiasm and the funding to explore the first steps of the Heath Hen revival; determining whether the bird was genetically distinct from its closest living relative, the prairie chicken.

THE HEATH HEN COULD COME BACK

COMMUNITY TOWN HALL EVENT, MARTHA’S VINEYARD, JULY 24, 2014

The Martha’s Vineyard Community convened in the summer of 2014 to discuss whether the extinct Heath Hen could be recoverable. The last of the Heath Hens died in 1932, but now in the 21st century, their DNA is fully restorable and the Heath Hen could come back. Thanks to recent and still-emerging breakthroughs in genetic technology, we told the Islanders that it is becoming possible the bring the extinct Heath Hen back to life. Its genome can be completely reassembled from DNA still viable in the 100+ museum specimens. The unique genes of the subspecies can be edited into the genome of its closest living relative, the prairie chicken, effectively resurrecting the Heath Hen. Full event report can be read here.

WHY HEATH HEN DE-EXTINCTION?

Conservationists have worked for decades to restore and maintain globally-rare sandplain grasslands and heathlands on the Massachusetts Islands, home to many rare species. These habitats need disturbance in the form of fire, grazing, or ocean salt spray to maintain their structure and biodiversity.

De-extinction of the Heath Hen will not only galvanize public interest in the conservation of the sandplain grasslands, but the revived Heath Hen would also fill an important conservation role in this unique ecosystem, as an indicator species. An indicator species is so intricately connected to its biocommunity and environment that it serves as a “thermometer” of an ecosystem’s health (biodiversity and bioproductivity). In short, if an indicator species is thriving in an environment, it tells conservation managers that all of the right habitat components are in place.

Heath Hens booming across New England once again will be a resounding song of conservation success for the endemic communities of the sandplain grasslands.

COULD ANOTHER SPECIES FILL THE SAME NICHE?

The primary reason Heath Hen de-extinction is more preferable than other forms of ecological replacement comes down to population viability. Its closest relatives, prairie chickens, require large, diverse populations with expansive grassland habitats and lekking grounds in order to thrive; they cannot live in small isolated pockets of habitat at low numbers. This is a major problem for the management of Midwestern populations of greater prairie chickens, which are in constant need of supplemental birds from larger flocks in Kansas and Nebraska. Without periodic augmentative genetic rescue, these isolated populations spiral rapidly into extinction. This is why historic transplants of prairie chickens to New England repeatedly failed.

While midwestern prairie chicken populations struggle in isolation, Heath Hens did not. The flock on Martha’s Vineyard grew from 50 birds to 2,000 after protections were implemented. Had the habitat been managed properly with fire and grazing, the birds would be here today. But the intense out-of-control wildfires of 1916 bottlenecked the population back to 50 birds. This second bottleneck compromised recovery, leading to extinction.

How did Heath Hens thrive in small flocks when their living relatives struggle under the same conditions? The Heath Hen must have exhibited differences in behavior, dispersal, and perhaps habitat exploitation. Heath Hens may have had differences in fertility genes or fewer deleterious genes lending to inbreeding problems. Discovering the genetic foundations of the Heath Hens adaptation to its habitat is key to its de-extinction.

Phases of Heath Hen De-Extinction

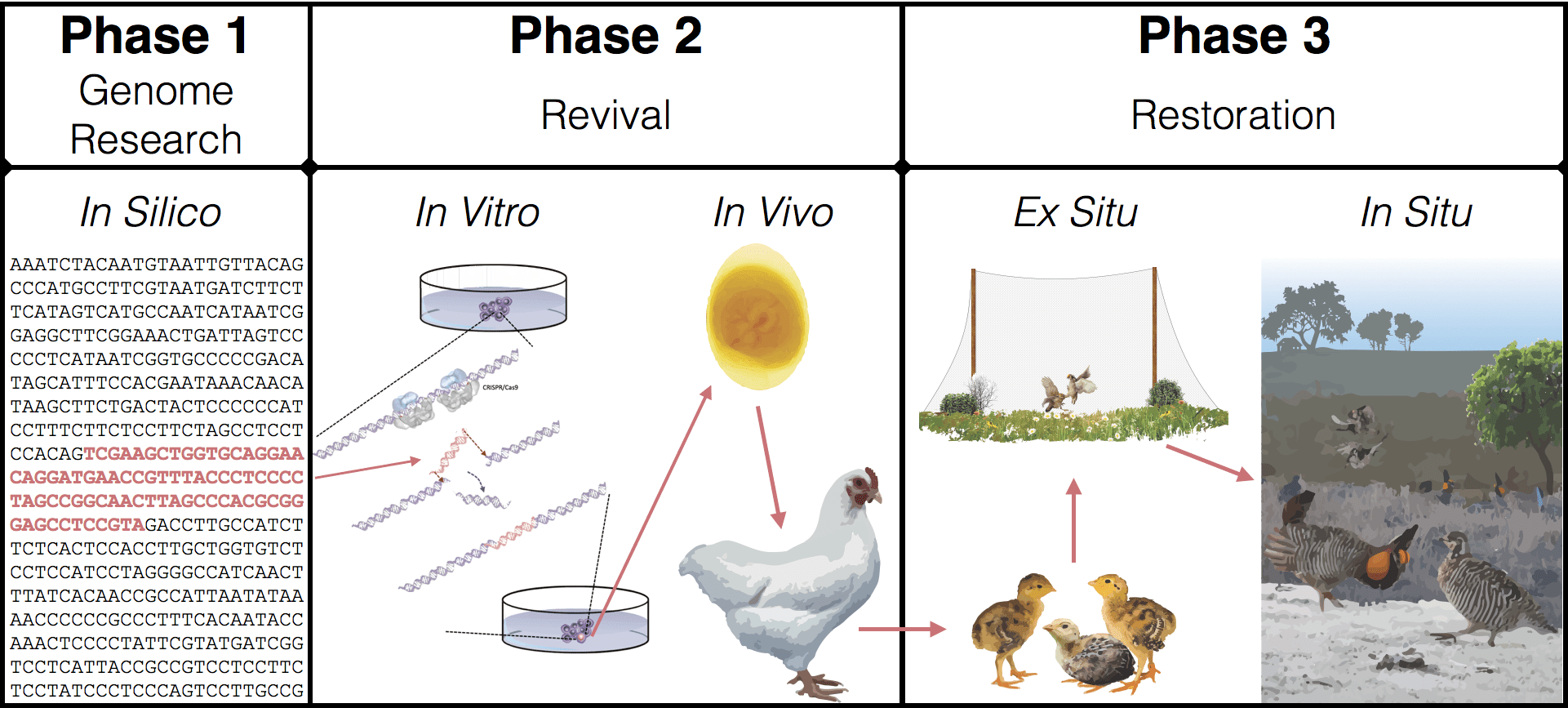

The phases of Heath Hen de-extinction encompasses five stages: in silico, in vitro, in vivo, ex situ, and in situ. These five stages can be grouped into three overarching phases given their overlapping and interdependent technologies and resources: genome research, revival, and restoration. This basic structure will be the same for all avian genetic rescue efforts, although the unique traits of every species will demand different innovative techniques at various stages in the process. Some aspects unique to the Heath Hen are:

Phase 1: Genome research (In silico research stages)

The goal of Phase One was to supply the genomic data necessary to understand the Heath Hen’s family tree. The Heath Hen is very closely related to living members of its genus, the North American prairie chickens, and unlike many other extinct birds, the Heath Hen has few visible differences from its living relatives. With limited historical records, not enough was known about the Heath Hen’s life history to distinguish unique behaviors from its living relatives. This meant there were no obvious traits to suggest which genetic pathways might be important for de-extinction. Sequencing and bioinformatic work is necessary to supply this missing information.

Our Phase One Genomics Study determined that the Heath Hen was indeed genetically distinct among its relatives, suggesting a genetic, and therefore possibly revivable, root to its localized adaptation to New England habitats.

Bioinformatic analyses are ongoing: Read more in Progress to Date.

Phase 2: Revival (In vitro and In vivo stages)

Phase 2 of Heath Hen De-Extinction is the Revival Phase, in which the primordial germ cells of the greater prairie chicken (the template species) are cultured in the lab; the essential genome-edits necessary to revive the lost Heath Hen ecotype are made in vitro; and edited greater prairie chicken cells are transmitted to the reproductive system of domestic chicken surrogates, which will breed and hatch the first generations of revived Heath Hens.

Initial Phase 2 research with partners Crystal Bioscience and Grouse Park in 2015 and 2016 yielded foundational results. The complexity of the avian reproductive technology challenge has led Revive & Restore to use the Heath Hen project as a catalyst for avian genetic rescue. As of summer 2019, Phase 2 has recommenced with a new partner, Texas A&M University. Grouse Park’s 2019 hatchlings will found the Texas research flock.

Phase 3: Restoration (ex situ and in situ stages)

The last surviving Heath Hens found refuge on the island of Martha’s Vineyard – home to the original Heath Hen preserve. Islands offer ideal reintroduction sites for research purposes; the natural barrier of ocean water provides a closed environment to contain early reintroduction studies. Martha’s Vineyard could be home to booming Heath Hens again someday. However, other nearby Massachusetts Islands may be better candidates for early Heath Hen reintroductions. Once the species proves its viability on the Massachusetts islands, restoration to the New England mainland can be considered.

Heath Hen Founding Funders

Revive & Restore would like to thank the following funders:

- Warren Adams

- G. Kenneth Baum and Ann Baum Foundation

- Lauren and John Driscoll

- Betsy and Jesse Fink

- Julie and Robin Graham

- Pamela Kohlberg and Curt Greer

- Gwen and Peter Norton

- Hadley and Brad Palmer