ABOUT THE SPECIES

A voracious carnivore, the Black-footed ferret (Mustela nigripes) preys upon the prairie dog (Cynomys spp.) to survive. Not only do they hunt prairie dogs for food, but they also overtake prairie dog burrows and use them for shelter. This reliance has led to several challenges for Black-footed ferrets, including exposure to introduced disease. Twice thought to be extinct, approximately 300 Black-footed ferrets are now living in the wild due to a conservation program led by the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). Still, the Black-footed ferret remains one of the most endangered species in the United States. Full recovery would signal a return to healthier ecosystems across the plains states in the US, Mexico, and Canada.

A FATE CLOSELY TIED TO ITS PREY

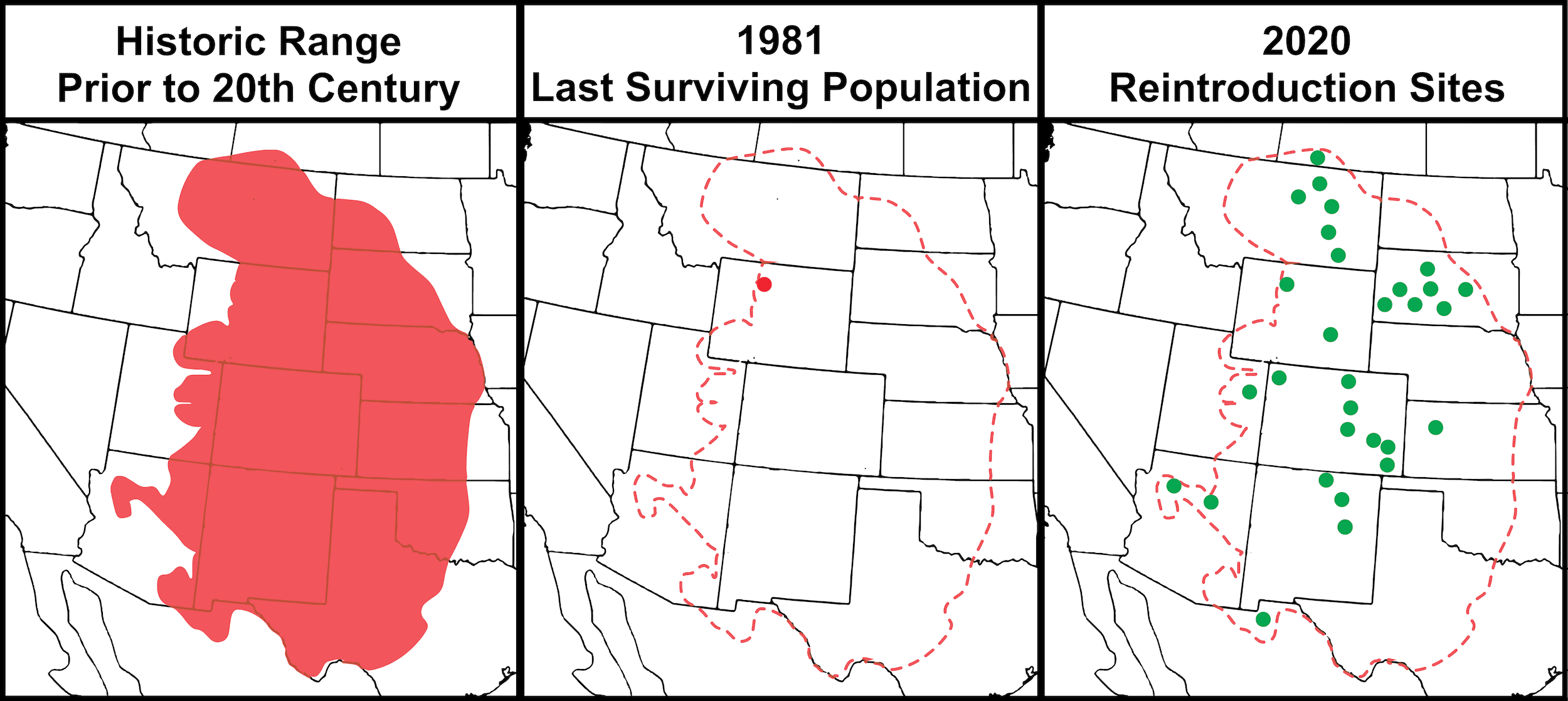

During the first half of the 20th century, misguided prairie dog eradication efforts on farms and ranches along with predator control campaigns decimated not only the prairie dog population but the Black-footed ferret population as well. Conversion of prairies to farmland has also gravely impacted both species. In 1967 the Black-footed ferret was placed on the U.S. Endangered Species List and in 1979 it was thought to be extinct. But in 1981, a population was discovered in Meeteetse, Wyoming after a rancher’s dog dropped the body of a Black-footed ferret on the porch of his owner’s home.

SAVING A SPECIES

Following that surprising discovery, the population was tracked down and the Wyoming Game and Fish Department initiated a bold conservation and captive breeding program. Between 1985 and 1987 conservationists rescued the last Black-footed ferrets surviving in the wild in Meeteetse so they could be bred in captivity to build up their numbers. To date, this and other participating centers have bred over 9,000 offspring, maintaining a captive population of approximately 250–350 breeding adults. Since 1992, the Black-Footed Ferret Recovery Implementation Team (BFFRIT) has reintroduced over 4,300 captive ferrets to 30 locations across Wyoming, South Dakota, Montana, Arizona, Colorado, Utah, Kansas, New Mexico, Canada, and Mexico. Each year, 150-220 Black-footed ferrets are preconditioned and reintroduced into the wild from the captive breeding population. There are approximately 300 Black-footed ferrets living in the wild today.

The many reintroductions represent a major success for the BFFRIT, which is working toward a goal of 3,000 wild Black-footed ferrets. Once the wild population reaches that size, the Black-footed ferret will be downlisted from endangered to threatened. The ultimate goal is to remove the species from the endangered species list to join the American Alligator and Bald Eagle among the Endangered Species Act’s conservation successes.

CHALLENGES TO FULL RECOVERY

For the Black-footed ferret to reach recovery, genetic rescue solutions are needed to overcome two major threats to the species: eroding genetic diversity and the threat of disease, particularly sylvatic plague.

A LACK OF GENETIC DIVERSITY

Because the total population size was once so small, the Black-footed ferret is now still threatened by an overall loss of genetic diversity. Of the last 18 wild ferrets brought into captivity, some were members of the same family and others died before successfully breeding. It is estimated that all living Black-footed ferrets today trace their ancestry to just seven founders.

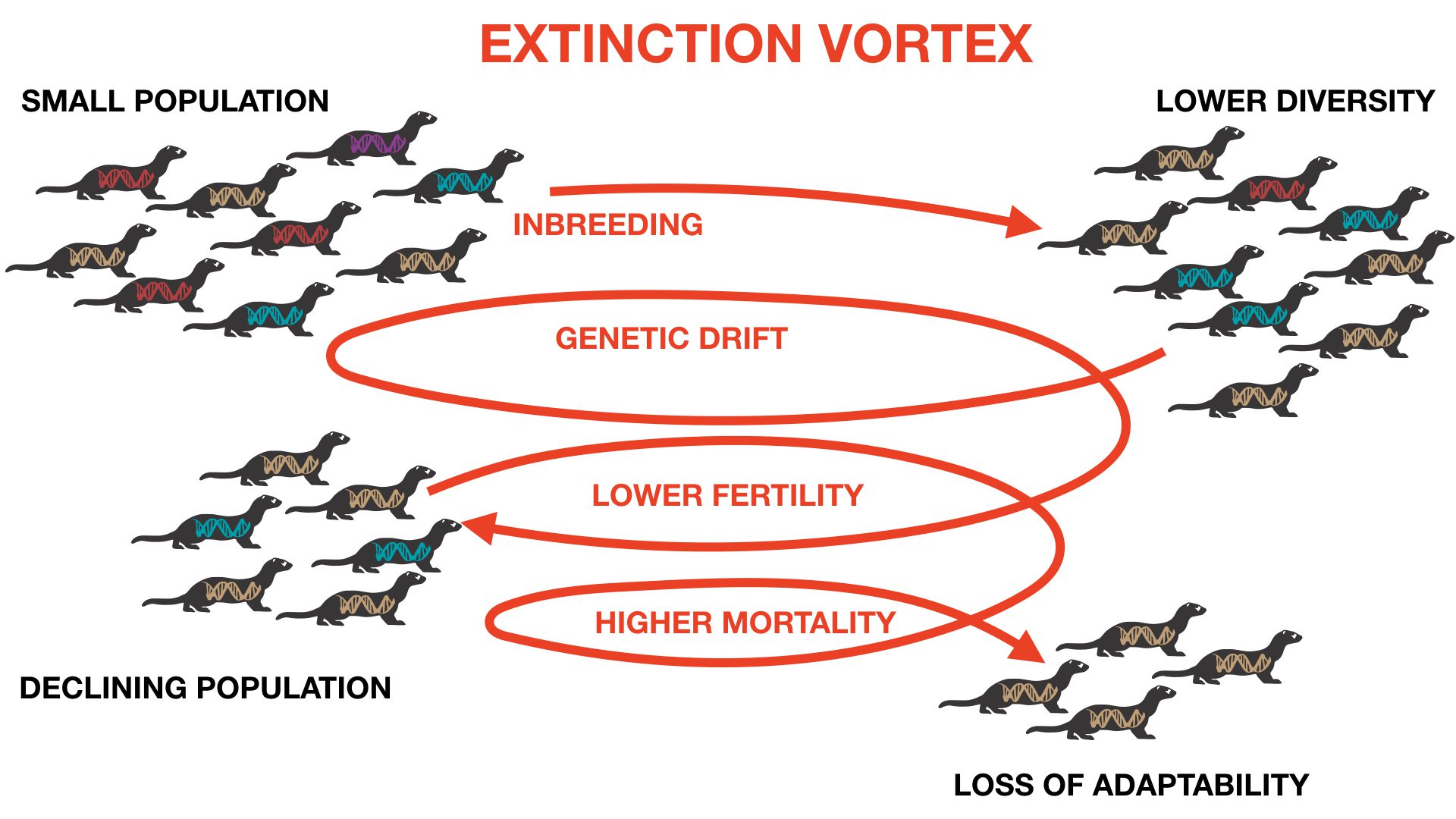

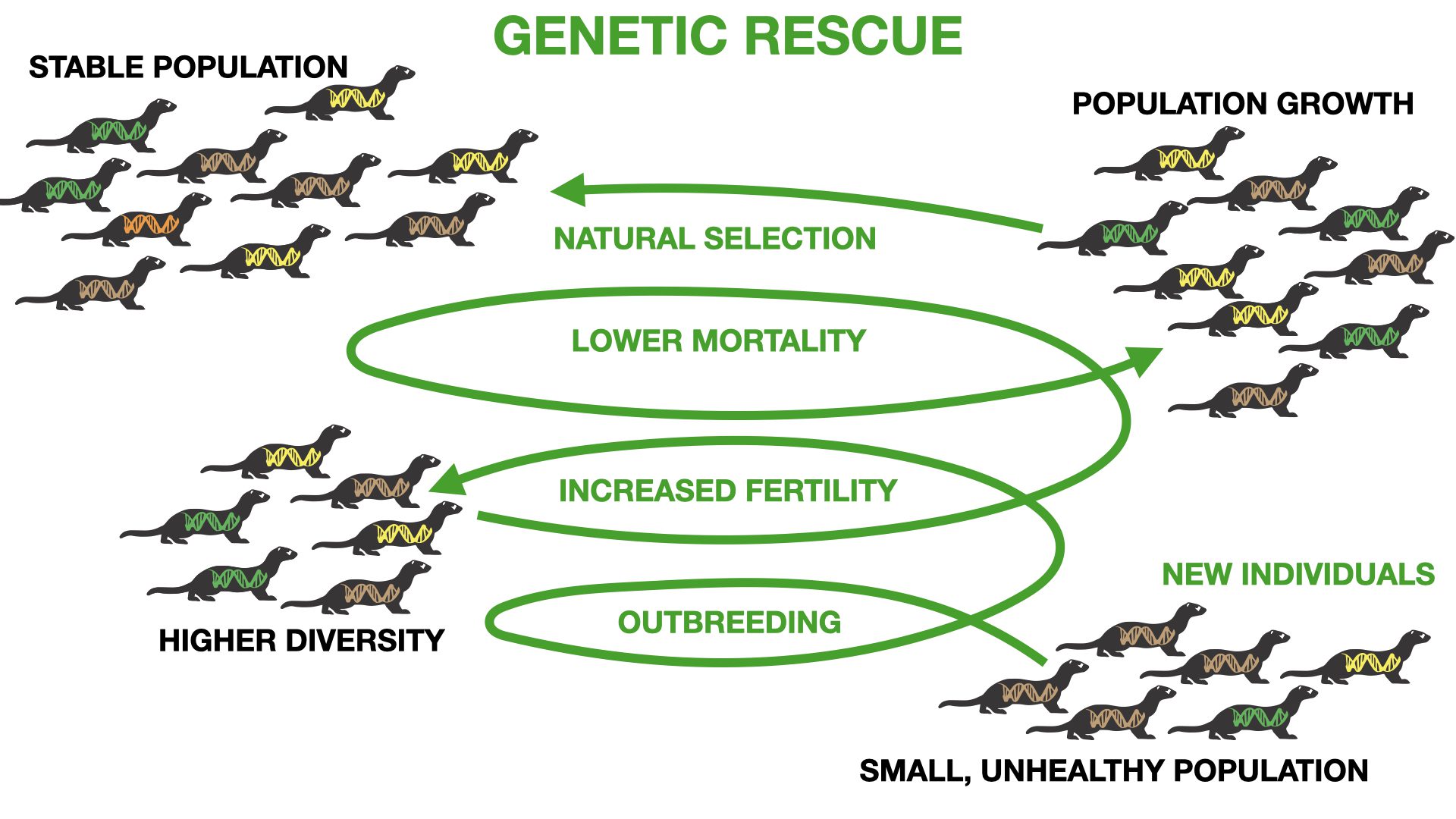

With such a limited gene pool, the small reintroduced Black-footed ferret populations are at risk of experiencing an “extinction vortex” without continued management. An extinction vortex is a progressive weakening of a species’ genetic fitness brought on by inbreeding, genetic drift, and an overall loss of genetic diversity stemming from small population size and lack of gene-flow from new immigrants. Staving off the extinction vortex requires continued supplementation to wild populations from captive breeding centers. However, maintaining the genetic diversity of captive Black-footed ferrets, and thereby helping wild populations, is the challenge that has prompted the aid of genetic rescue biotechnologies. Genetic rescue can help reverse or prevent an extinction vortex.

It’s estimated that Black-footed ferrets eat 100 prairie dogs annually in the wild. (USFWS)

The species requires prairie dogs and prairie land like this expanse on the Hogg family ranch in Meeteetse, Wyoming, where the last wild population of ferrets was discovered in 1981. The BFFRIT reintroduced ferrets here in 2016. (USFWS)

From a founder population of seven individuals from Meeteetse, Wyoming, the captive breeding program has released hundreds of ferrets to 30 reintroduction sites across their historic range.

On October 30, 2013, the USFWS released 30 Black-footed ferrets onto a ranch in Colorado, beginning a “safe harbor agreement” that allows private and Tribal landowners to volunteer their lands for reintroduction. (USFWS)

When the captive breeding program first began, Wyoming Game and Fish had the foresight to biobank cell lines, semen, and ovaries. Sperm samples archived for decades at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute have been used to recover lost genetic diversity from the founders through artificial insemination, the first efforts demonstrating the value of reaching back in time for genetic rescue. Historic cell lines stored at the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Frozen Zoo® since the 1980s are the focus of the Revive & Restore genetic rescue cloning efforts to bring new founders into the population, thereby improving the current gene pool.

THE THREAT OF DISEASE

The ultimate survival of wild Black-footed ferret populations is jeopardized by disease. Aside from habitat loss, sylvatic plague (Yersinia pestis) is the single largest challenge to the species. The plague bacterium was accidentally brought to North America from Asia by humans in the late 1800s. It is the same pestilence that devastated Europe in the 14th century. Nearly 150 years later the disease is widespread over the western United States and Great Plains. Black-footed ferrets contract the disease primarily from their prey, the prairie dog. While prairie dog populations are large enough and diverse enough to adapt to plague, and there is evidence that some populations do exhibit resistance, this is not possible for the Black-footed ferret. While the domestic ferret appears to be immune to plague, Black-footed ferrets have always been highly susceptible. That fact, coupled with the lack of genetic diversity indicates that interventions that protect them from plague infection will continue to be needed to achieve full recovery.

The complex epidemiology of plague and its widespread abundance on the landscape makes it impossible to eradicate. This reality, coupled with the Black-footed ferret’s extreme susceptibility to the disease, means that successful recovery of the Black-footed ferret will depend on creating improved plague tolerance for this species. The consensus of dozens of scientists and conservationists is that success will not be achieved by treating any one link in the chain of disease transmission. The ferrets must be treated directly. The good news is that a vaccine has been developed that provides Black-footed ferrets with lifelong immunity to plague. This proves that the Black-footed ferret immune system can be trained to recognize and fight plague.