Why Revive Extinct Species?

The Case for Reviving Extinct Species

The Case for Reviving Extinct Species

by Stewart Brand

National Geographic News (Published March 11, 2013)

Thanks to new developments in genetic technology, DNA may eventually bring extinct animals back to life. Only species whose DNA is too old to be recovered, such as dinosaurs, are the ones to consider totally extinct, bodily and genetically.

But why bring vanished creatures back to life? It will be expensive and difficult. It will take decades. It won’t always succeed. Why even try?

Why do we take enormous trouble to protect endangered species? The same reasons will apply to species brought back from extinction: to preserve biodiversity, to restore diminished ecosystems, to advance the science of preventing extinctions, and to undo harm that humans have caused in the past.

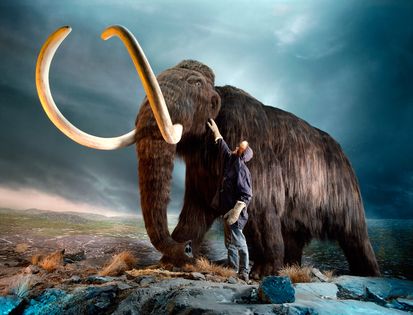

Furthermore, the prospect of de-extinction is profound news. That something as irreversible and final as extinction might be reversed is a stunning realization. The imagination soars. Just the thought of mammoths and passenger pigeons alive again invokes the awe and wonder that drives all conservation at its deepest level.

Furthermore, the prospect of de-extinction is profound news. That something as irreversible and final as extinction might be reversed is a stunning realization. The imagination soars. Just the thought of mammoths and passenger pigeons alive again invokes the awe and wonder that drives all conservation at its deepest level.

Then, there’s the power of good news. The International Union for Conservation of Nature is adding to its famous “Red List“ of endangered species a pair of “Green Lists.”

One will describe species that are doing fine as well as species that were in trouble and are now doing better, thanks to effective efforts to help them. The other list will describe protected wild lands in the world that are particularly well managed.

Conservationists are learning the benefits of building hope and building on hope. Species brought back from extinction will be beacons of hope.

Useful science will also emerge. Close examination of the genomes of extinct species can tell us much about what made them vulnerable in the first place. Were they in a bottleneck with too little genetic variability? How were they different from close relatives that survived? Living specimens will reveal even more.

Techniques being developed for de-extinction will also be directly applicable to living species that are close to extinction. Tiny populations can have their genetic variability restored. A species with a genetic Achilles’ heel might be totally cured with an adjustment introduced through cloning.

For instance, the transmissible cancer on the faces of Tasmanian devils is thought to be caused by a single gene. That gene can be silenced in a generation of the animals released to the wild. The cancer would disappear in the wild soon after, because the immune animals won’t transmit it, and animals with the immunity will out-reproduce the susceptible until the entire population is immune.

Some extinct species were important “keystones” in their region. Restoring them would help restore a great deal of ecological richness.

Woolly mammoths, for instance, were the dominant herbivore of the “mammoth steppe” in the far north, once the largest biome on Earth. In their absence, the grasslands they helped sustain were replaced by species-poor tundra and boreal forest. Their return to the north would bring back carbon-fixing grass and reduce greenhouse-gas-releasing tundra. Similarly, the European aurochs (extinct since 1627) helped to keep forests across all of Europe and Asia mixed with biodiverse meadows and grasslands.

The passenger pigeon was a keystone species for the whole eastern deciduous forest, from the Mississippi to the Atlantic, from the Deep South clear up into Canada. “Yearly the feathered tempest roared up, down, and across the continent,” the pioneer conservationist Aldo Leopold wrote, “sucking up the laden fruits of forest and prairie, burning them in a traveling blast of life.”

Such animals can also serve as icons, flagship species inspiring the protection of a whole region. The prospect of bringing back the aurochs is helping to boost the vibrant European “rewilding” movement to connect tracts of abandoned farmland into wildlife corridors spanning national boundaries.

A Nenets boy touches a mammoth carcass outside the Shemanovsky Museum in Russia. Photograph by Francis Latreille, International Mammoth Committee/National Geographic

Similar projects to establish “wildways” joined across American eastern states could benefit from the idea of making the region ready for passenger pigeon flocks and flights of the beautiful Carolina parakeet, once the most colorful bird in the United States.

Wilderness in Tasmania is under pressure from loggers and other threats. The return of the marvelous marsupial wolf called the thylacine (or Tasmanian tiger), extinct since 1936, would ensure better protection for its old habitat.

The current generation of children will experience the return of some remarkable creatures in their lifetime. It may be part of what defines their generation and their attitude to the natural world. They will drag their parents to zoos to see the woolly mammoth and growing populations of captive-bred passenger pigeons, ivory-billed woodpeckers, Carolina parakeets, Eskimo curlews, great auks, Labrador ducks, and maybe even dodoes. (Entrance fees at zoos provide a good deal of conservation funding, and zoos will be in the thick of extinct species revival and restoration.)

Humans killed off a lot of species over the last 10,000 years. Some resurrection is in order. A bit of redemption might come with it.