2016 Year End Report by Stewart Brand

In 2016 Revive & Restore went ever deeper into its multiple genetic rescue projects bringing biotech to wildlife conservation. It was all made possible by generous donations from remarkable individuals and organizations over the last four years.

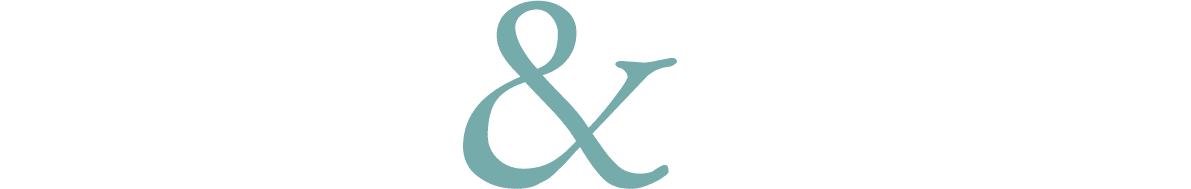

This diagram shows six species now being genetically rescued. Left to right: 1) the Black-footed Ferret endangered by inbreeding; 2) the Asian Elephant threatened by disease; 3) the nearly extinct Northern White Rhino (led by San Diego Zoo Global); 4) the extinct Heath Hen; 5) the extinct Passenger Pigeon; and 6) the extinct Woolly Mammoth.

Our major news: In 2017 Revive & Restore will fledge gratefully from The Long Now Foundation and become an independent nonprofit that can provide a wide range of genetic rescue services for wildlife conservation clients. We are partnering with a major biotech firm to deploy and expand the capabilities we have been building since our founding in 2012.

Here are some headlines from the report below:

- Our 9-month study showed there is a market for a full suite of biotech services for biodiversity conservation.

- To set up as a standalone entity offering those services, Revive & Restore will need to raise about $1 million.

- At meetings we co-organized in Hawaii, we explored: 1) Saving native birds from avian malaria by eliminating the invasive mosquitoes that carry the disease; 2) Eradicating invasive rats and mice from ocean islands with gene-drive methodology; 3) Saving Hawaii’s keystone Ohi’a trees from an invasive fungus.

- Our work on protecting the Black-footed Ferret from inbreeding and disease took a leap forward.

- The project to bring back the extinct Heath Hen is approaching a major breakthrough.

- Ben Novak’s master’s thesis showed the crucial ecological role that Passenger Pigeons played.

- Work on Woolly Mammoth de-extinction and an Asian Elephant disease vaccine proceeded at George Church’s Harvard lab.

- We co-authored a significant paper on the growing need in conservation for new biotech tools.

The new standalone Revive & Restore

Last March we hired Angus Parker (president of the board at Island Conservation) to do an extensive survey of the new genomic tools becoming available, the specific ways they can be applied to conservation problems, the species that most would benefit from genetic help, the variety of potential clients, and the resources necessary to execute at scale.

We concluded that an expanded Revive & Restore, in partnership with biotech organizations, will be able to offer services that include Genetic Insight (DNA sequencing and analysis), Biobanking (tissue collection and cell culturing), Advanced Reproductive Services (cloning and germ-line transmission), and Genome Engineering (CRISPR, gene-drive, etc.) Applications include restoring genetic diversity, augmenting adaptation to climate change, conferring resistance to disease, and extirpating harmful invasive species.

Our role is to match the right team of experts to each project, drawing on the worldwide cadre of 150 conservation biologists, molecular biologists, veterinarians, and bio-ethicists we have been working with. We will also ensure that each project is transparent to the public and meets regulatory requirements.

To make the shift from a boutique operation to a viable full-service organization, Revive & Restore must now expand its grasp to match its reach. Conservation worldwide is said to spend about $52 billion annually. Growing Revive & Restore to the point where we can begin to serve that market well will take an estimated $1 million of development funding.

We organized the only biotech workshops at the massive IUCN Conservation Congress in Hawaii

The September mega-conference (10,000 participants) of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature was the largest in its 68-year history and the first on US soil. Hawaii was chosen in part because it is regarded as “the extinction capitol of the world.” Accordingly, our director Ryan Phelan organized two meetings focused on three Hawaiian conservation problems, with the purpose of showing to the world conservation community and the Hawaiian public (famously averse to GMO crops) the potential effectiveness of new biotech tools for protecting wildlife. Overflow audiences came to both meetings.

We assembled a problem-specific set of specialists from conservation biology, molecular biology, and government for each of the three topics.

1) Avian malaria and avian pox, carried by invasive mosquitoes, has pushed a huge percentage of native Hawaiian forest bird species to the brink of extinction, and their mosquito-free refuges on mountain tops are shrinking due to global warming. Our meetings examined the variety of new genetic techniques developed to cure human malaria and Zika virus by eliminating mosquitos—such as Oxitec’s sterile males, wolbachia applications, and gene drives—and looked at how they might be applied to protect Hawaiian birds. (Following the IUCN Congress we co-organized an additional meeting in depth on the subject, sponsored in part by the National Park Service. A roadmap of recommendations is emerging from that meeting, and Michael Specter blogged about it for the The New Yorker.)

2) A rapidly spreading invasive fungus referred to as “Rapid Ohi’a Death” has killed thousands of Ohi’a trees, the keystone species of the Hawaiian forest, and threatens to deforest the whole archipelago. Dr. Samuel ‘Ohukani‘ōhi‘a Gon of The Nature Conservancy explained the sacred standing of the Ohi’a in native Hawaiian culture, and Andy Newhouse described the success the State University of New York has had genetically editing blight-proof American chestnut trees, heading off their extinction by an invasive fungus.

3) All ocean island ecosystems, including Hawaii’s, are profoundly threatened by invasive rodents. Karl Campbell from Island Conservation reported on his organization’s investigation into using gene-drive technology as potentially the most targeted, effective, and economic technique for eliminating invasive mice and rats. MIT’s Kevin Esvelt urged caution with “global” gene drives and described his design of a more nuanced method he calls “daisy drive.”

Genetic rescue of Black-footed Ferrets is moving from roadmap to reality thanks to a new ally, Intrexon

Usually referred to as “America’s most endangered mammal,” Black-footed Ferrets have successfully been bred in captivity and returned to the wild, but they are suffering from inbreeding and from an exotic lethal disease, sylvatic plague. If these are not corrected, the species can never succeed in the wild. At an April 2016 meeting we co-organized with San Diego Zoo Global, a plan was set to ensure wild survival of the Black-footed Ferret through cloning and genetic engineering. That proposal has been submitted to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

Thanks to geneticist Oliver Ryder, the Frozen Zoo at San Diego Zoo Global has living cell lines of two Black-footed Ferrets that died 35 years ago. Last year we showed that if those two were cloned back to life, they would add two new unique animals to the seven “founders” of all currently living ferrets. They would enrich the gene pool and help head off the “extinction vortex” that can trap inbred populations. Intrexon, the world’s most versatile biotech firm, offered to do the cloning work and to explore ways to possibly introduce genetic resistance to sylvatic plague in later generations of ferrets. Both accomplishments would be revolutionary for wildlife conservation.

Our work with primordial germ cells for Heath Hen de-extinction is on the brink of opening the way to genetic rescue for birds

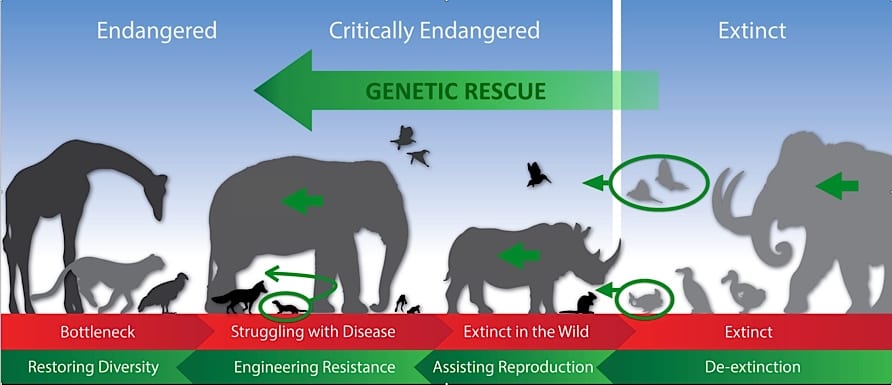

Getting edited genes into living birds cannot be done with cloning, as it is with mammals. The workaround, which involves creating “chimeric” surrogate parents that effectively have the gonads of the target species, has still to be proven with wild birds. We are poised to begin the final stages of proving it can be done.

In 2016 we received 72 prairie-chicken eggs from Grouse Park in Idaho, where our prairie chickens are bred in captivity. Crystal Bioscience in California extracted primordial germ cells from the embryos in those eggs and proved 1) they can be successfully kept alive in a special culture medium, and 2) they really are primordial germ cells. We expected the work to take two or three years, but it took only one. We are ahead of schedule.

The next stages—proving that the technique can get genes edited with a fluorescent marker into living wild birds—could be completed as early as 2017. Success will be major scientific news. Here’s some detail on how the breakthrough can be proved using a domestic-chicken rooster as the surrogate male parent:

The next step after this will be to start working with Heath Hen genes.

For his Master’s thesis at University of California Santa Cruz, Ben Novak proved that Passenger Pigeons were a significant “ecosystem engineer” of America’s eastern forests

According to our staff scientist Ben Novak, America’s great eastern forest has mostly grown back from its 19th-century deforestation. But it is structurally different now, with lower biodiversity than before, in part because Passenger Pigeons are no longer around. They used to roost and nest in such dense flocks that they broke branches and produced thick layers of dung in large areas. Those fertile clearings helped produce a patchwork mosaic of forest openings that provide a home for many more species. Here is Ben’s illustration of the healthy disturbance that the pigeons brought (and could bring again) to closed-canopy forests:

In addition, the analysis of Passenger Pigeon DNA at Beth Shapiro’s UC Santa Cruz lab shows that the birds were highly resilient as glacial periods came and went in North America. They were not dependent on any particular vegetation, and that makes them fine candidates for return to the contemporary eastern forest. Ben points out: “The goal of de-extinction is: to restore vital ecological functions that sustain dynamic processes producing resilient habitats, and to increase biodiversity and bioabundance.“

Progress continues at Harvard on reviving the Woolly Mammoth and saving Asian Elephants from a deadly virus

George Church and his postdoc team at Harvard Medical School have identified more Mammoth genes for cold-adaptation and edited them into elephant cell lines. Their Asian Elephant project has completed the re-assembly of the genome of the herpes virus that is killing many young elephants, so now the development of an effective vaccine will be able to proceed for the first time.

Articles and books about genetic rescue and de-extinction continue to multiply

There are now five good books on de-extinction. Two new ones this year are THE UNNATURAL WORLD by David Biello and BRING BACK THE KING: THE NEW SCIENCE OF DE-EXTINCTION, by Helen Pilcher. (I blurbed her book: “With humour and accuracy, Helen Pilcher surveys the wondrous array of wildlife de-extinction and preservation projects that employ current breakthroughs in genomic technology.”)

The New York Times op-ed page had an excellent report on Revive & Restore’s projects by Hillary Rosner titled “Tweaking Genes to Save Species.”

Ryan Phelan participated in an IUCN-sponsored workshop in Italy which resulted in a paper she co-authored titled “Is It Time for Synthetic Biodiversity Conservation?” published in Trends in Ecology & Evolution.

Our answer to the question in that title is yes, now is the time. In 2017 we aim to move on from advancing the science of “tweaking genes to save species” to deliver at scale for government agencies and non-profit conservation organizations around the world. To build that capacity we need to raise $1 million.