Prepared Remarks: September 3, 2016

Text by Sam Gon

Anuanu ke kiamanu i ka wao lipolipo,

hoʻopulu wale i ke kulukulu uhiwai;

ʻimi i ka ʻōʻō hulu melemele,

ka pā hane mai i ke ahe mālie,

a he leo, he mai e…

Aloha mai kākou!

In the Kumulipo, the long creation chant of Hawaiʻi, forest birds are mentioned very early, long before the major Hawaiian gods, and therefore epochs before people. Thus birds are elders of even the gods, and in Polynesian culture, and many ancient cultures of the world, elders are revered, respected, and cared for.

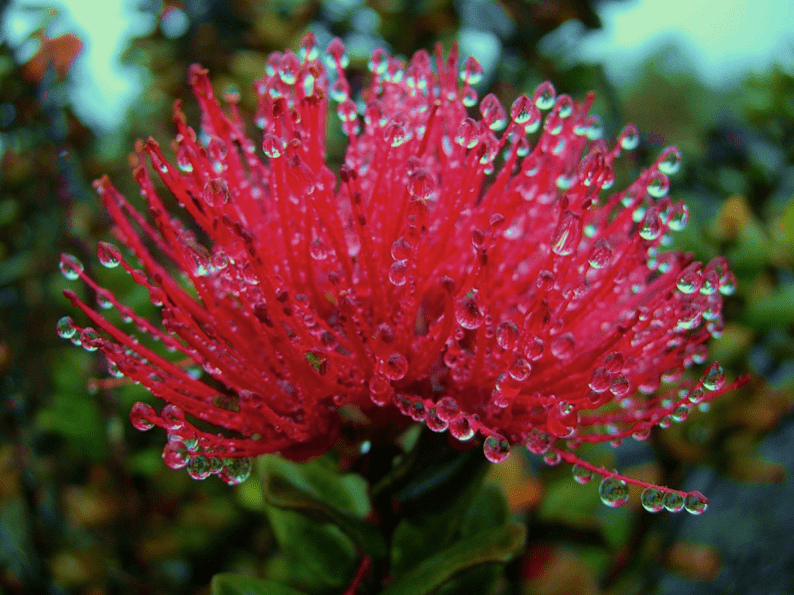

The association of Hawaiian forest birds with the gods extends to material culture, perhaps best known as expressed in the intricate and beautiful feather work of Hawaiʻi, provided by such birds as the ʻiʻiwi shown here, as well as the mamo, the ʻōʻō, and others. The association of our forest birds with the sacred also places them deeply into traditional knowledge; into stories in which birds are the kahu, or caretakers of goddesses, and alternately, where they serve as the aerial spies for forest gods. In traditional proverbs and wise sayings that teach important moral lessons, or make observations on the human condition, our Hawaiian forest birds remark on everything from the majesty of royal people, to admonitions against having a sour disposition.

So, whether as the kinolau, or physical manifestations of Hawaiian gods and ancestors, as the source of remarkable beauty in traditional Hawaiian feather work, or their role in Hawaiian knowledge and traditions, our forest birds represent a irreplaceable biocultural resource as well as a textbook example of island adaptive radiation. When such a legacy is threatened with obliteration, we must take steps to identify the solutions where we can, and apply them.

It has long been known that mosquitoes, introduced to Hawaiʻi less than two hundred years ago, carry foreign bird diseases, avian malaria and avian pox, which even today make the mosquito-ridden lowlands a death zone for our endemic forest birds. With human mosquito-borne diseases such as dengue, Zika, and chikun-gunya on the rise and threatening us directly, we can think on the fact that for our forest birds, such dreadful prospects have been at work for over a century, killing one of our invaluable cultural and natural assets, but because these diseases didn’t pose an immediate human health risk, and because we had no real tools for dealing with them, we could do nothing about it.

But today, that has changed…